Name Your Ducks in a Row

This is the first in a series of articles on how, as a freelancer, I have improved and optimized some of the more mundane aspects of running my design business.

This is the first in a series of articles on how, as a freelancer, I have improved and optimized some of the more mundane aspects of running my design business.

Repeat business is a blessing for any business owner. But when you are asked to retrieve a project that you worked on 2 years ago you get this sinking feeling inside.

Here, I outline my file naming convention, archival, and retrieval strategy…

As independent business owners, we’re often faced with tasks that, apparently, have nothing to do with our creative line of work. Eventually, we find methods of reducing our time spent on the mundane in order to maximize our creative “play time.”

One of the most obvious, if you work with computers, is how to organize your files in a way that makes it easy to find a project later down the road. Concise file names are critical to the workflow of a well-oiled creative. A well-named file can tell you — in 32 characters or less, the following: what client and project it belongs to, particular element (ad, logo, photo, etc.), age (version number), and what kind of file it is.

How do we relay all this in 32 characters? Why is that necessary when today’s operating systems support 256 characters or more? It’s true that you may get away with longer filenames. Why not write a paragraph, explaining the file, as the name? Two reasons: legibility; and compatibility. When reading through a list of files it is faster to decipher a neatly organized string of letters and numbers than to read a story. Secondly, I have found a software package or two that chokes on a file with more than 32 characters. It read the file with no problem, but when it came out the other end the name was gibberish. The software could not write more than 32 characters in the file name.

The Name

We all have names. We all have used a form of shorthand when leaving our mark on trees, in bathrooms, on our expensive cameras. The monogram is an excellent device that we can apply to both the client and project. Representing each with a three letter combination allows us to mark all relevant files to that client and project in only eight characters.

Yes, art students, eight characters. To make our filenames more legible we’ll separate each three character code with an underscore so that “glrtxp” becomes “glr_txp_” — eight.

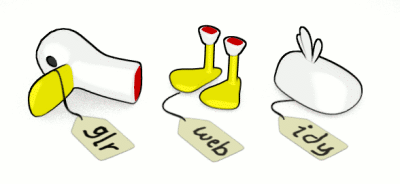

To illustrate, this is how a draft of an article might look like for this web site:

glr_txp_fln_draft_v01.rtf

Here’s the formula:

client_project_part_element_version#.filetype

From left to right the name is built with general information, to specific. In some cases “part” and “element” merge, especially if it’s a small project. In other cases, more depth might be needed. There is flexibility as well. Notice I escaped the three character convention for “draft.” The characters I saved when specifying client, project, and part, I spent on communicating the element—the specific information. It is easy to remember the client and project. Less easy to remember a particular element you worked on two months ago.

Benefits

- Marvel as you scroll through folders, full of your files, with ease

- Now finding files on your system couldn’t be easier. Find all files by client, project, or type — if you standardize on codes for your services: idy – identity; web – web site, etc.

- Finding files on backup media is also streamlined when using media cataloging software

Tips

- Decide at the start of every project and jot the formula for naming files, for that particular project, with examples. Send this as a memo to your client and any collaborators

- Keep a log of monograms that are used to prevent duplicate client codes and to standardize job types

- Use versioning to combat file corruption. Whenever making a major change to a file, save and increment the version number

Filed under: Process,

Filed under: Process,